Wednesday morning, and it’s minus 8° Centigrade. The sort of snowstorm seldom seen in the West, perfect weather for an interview with Sonia Wieder-Atherton about D'Est en musique. As I approach her front door, I hear the cello. That tone so deep, forged through years of commitment, two of those years in 1980’s Moscow, a tone that no doubt continues to deepen. I suddenly wish she would keep playing, unaware that I’m waiting outside. But it’s freezing, and we have an appointment, so I show my face at the window, she sees me, the sound ceases, a door opens. The last echoes fade, to be replaced by a flesh and blood meeting of unforgettable intensity.

Long before D'Est en musique, there was Chantal Akerman’s feature film D’Est, made with very limited resources in early 1990’s Eastern Europe. She travelled the Eastern Block from spring through endless winter. There is no dialogue, but the shots are intriguing. People stand in queues, walk about or wait for a bus, often in the dark, often in the muddy snow. Others make tea, look into the camera, show us round their homes. And sometimes you simply see a window. Something has certainly happened, but we never find out what – the documentary frequently veers close to the fictional. ‘I recognised them, those Eastern faces, they reminded me of other faces. And that waiting in line, those stations, they reminded me, reflected the impression, of that void in my own history…’ (Chantal Akerman, Autoportrait en cinéaste). Like Russian music, that can so powerfully depict what words cannot, when explicit detail is absent: everything finds its expression in a land without words.

Sonia Wieder-Atherton had already played a role in the creation of this film: ‘Her D’Est fascinated me, without the music. It was like an elegy for me, quite extraordinary. We chose the music together; we have some Chaliapin, we have Natalia Shakhovskaya playing in there.’ The cellist knew the region well, thanks to her studies in Moscow, at a time when she had to convince the Foreign Ministry to let her go on an exchange between France and the USSR. ‘I was drawn to the East. Aside from the literature, there was that sound I heard: so different, like a strange language with a melodiousness that moved one, but whose mystery remained impenetrable.’

‘There I discovered a fundamentally different system of education, one that demanded much more time: a prolonged exploration of your relationship with a work, with the contrast, with your fears, with the world – far beyond the art of simply playing your instrument well. On the one hand, this was an unusually intense and highly structured way of working, and on the other, a process that emancipated many horizons, transmitted with a certain urgency. Plus the fact of coming face to face with oneself while abroad, getting to know the regime, the country, the culture, the very harsh daily existence. Those are forever interwoven with my experience.’ Russia remains ever-present in the cellist’s life and she often returned there before the invasion of Ukraine in 2022, a subject we will come back to. What now remains with her, more than her commitment to the Slavic repertoire, is that unique approach to sound.

The D’Est soundtrack consists almost entirely of direct sound, the real world sounds recorded during filming. Dialogue is occasionally captured, but only in the background. Sometimes it’s the sound of a spoon, or of someone pushing a cart. There is music too, right from the start. Almost every time we hear music, we see the source on screen: a concert, a family gathering, or a dance. And whenever music is heard over the images, the film assumes a different direction and potency. The long static images, the tracking shots that stretch time, these all demand music – which brings us to tonight’s project.

‘D’Est en musique is really the result of a collaborative creative process. Our two worlds merged to create this work’, continues Sonia Wieder-Atherton. ‘I told Chantal about my dream of attempting something with music on D’Est. She gave me a completely free hand and I then spent a week experimenting with various approaches.’ The cellist gave form to her intuitions, tested a number of pieces with various scenes: only during this dialogue did she realise what doors might thereby be opened, and what simply wouldn’t work. ‘I still remember the scene I showed Chantal when she visited me, that ball at the end in the Grand Hotel in Moscow. We played a Prokofiev Adagio over it, instead of the scene’s direct sound. And Chantal was amazed. She found it wonderful. She said we had to continue our collaboration.’

‘Chantal Akerman re-edited her film for D’Est en musique: we selected the music, the moments, the breaks and the end. Chantal even changed the film’s sequencing slightly, so as to merge better with the music. We left some scenes in silence; we found that beautiful. We created something totally new, a sort of visual concert.’ The point where artistic boundaries make way for a new form of perception is where Sonia Wieder-Atherton feels most alive. ‘Works from the repertoire are like travelling companions – I take them with me wherever I go, confronting the world with what they have to say.’ Evoking wonder also means bringing the power of the work to the fore in a new light.

We would now describe it as an immersive artistic installation rather than a visual concert: ‘The film is projected onto a dark screen giving a more spooky effect with its transparency and darker tint, but also because of the “double projection” of the see-through screen, which floats as if echoing the sound. No one could believe it when Chantal, who also designed the lighting, wanted the ensemble to be in darkness, and to get darker until barely visible. Thus there is a long tracking shot in Moscow station, with its great, white-marble walls. When we see the marble, we also discover, amidst the pure whiteness, the musicians behind the screen, before they fade to silhouette and then again return to visibility. It’s as if you’ve stepped inside the screen, as if you’re floating in the Moscow snow. Chantal played around a lot with shadow and half-shadow.’

D’Est takes us on an uninterrupted visual journey, while D’Est en musique sometimes leaps from one country to another, turns back or cultivates the art of the detour. Which is still a journey of sorts. ‘I feel the music accurately reflects the film’s episodes, as if giving us an idea of what the personages might be thinking. When they stand in a queue, when they look you in the eye, it’s as if the music is imagining what might be happening deep inside themselves.’

The 2024 version cannot be the same as the original: we cannot ignore the world situation… ‘D’Est en musique begins in a Ukrainian potato field, women working the harvest. I found that we couldn’t simply leave the image as it was: the opening scenes were filled with Russian music, as if Russia had swallowed up the whole of Eastern Europe. I’ve therefore made some small adjustments without changing the essence of the film: it now opens with a Kaddish by Ravel on Ukrainian melodies, for me a powerful way to acknowledge the present tragedy. If Chantal was still with us (the filmmaker passed away in 2015), I believe that together we would have done exactly what I’ve done now, because she would have certainly wanted the same – but I’ve had to imagine her presence. Chantal’s work and her relationship to the world was always about connection with that world. And if we are connected to the world, then we cannot simply ignore this monstrous war. During recording, she said she was drawn to the East “so long as there’s still time”. That statement was frighteningly prophetic.’

Lise Bruyneel, translated by Patrick Goddard

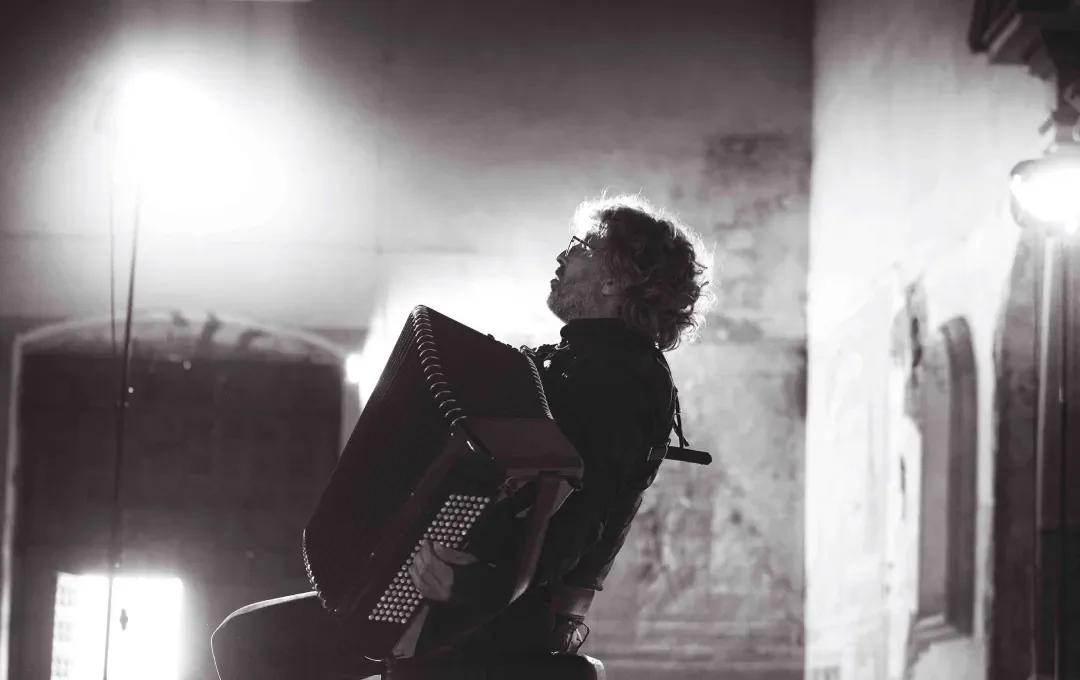

Image © Carole Bellaiche / film stills D'Est - collections CINEMATEK © Fondation Chantal Akerman